The Making of Another Way

On May 6, 2025, Another Way: Building Companies That Last...and Last...and Last, by Dave Whorton with Bo Burlingham was released to the public. Their book tells the story of Dave’s journey from Venture Capital’s epicenter in Silicon Valley to founding Tugboat Institute®, an organization dedicated to bringing together, supporting, and championing Evergreen® leaders and their Purpose-driven, Private, enduring companies.

In this conversation moderated by Tugboat Institute member Mel Gravely, Executive Chair of Triversity Construction, Dave and Bo share their experiences conceiving of this project, their working relationship and the process of writing it, and what they hope it will accomplish in society. Mel deftly leads the two friends and co-authors through topics that will touch and inspire you, and that will help you better understand the foundation and the aspirations of the Evergreen movement.

Watch and be inspired to read this book and support this important movement.

Find the Tool That Will Help You Grow

I started Jack Brown’s Beer & Burger Joint in 2009 with my childhood best friend Mike Sabin. We were both feeling at the end of our ropes with our jobs at the time, and I called him after one particularly bad day. In the space of one conversation, we decided, let’s finally open the bar together?! Initially, we just thought it would be fun to run a bar for a while. We never imagined it would turn into what it has become today: a company with multiple locations across Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Alabama, and Tennessee, with over 500 employees.

The early days were wild and fun, and we learned as we went. Eventually, however, as we started to experience success and grow, and especially when we surpassed 10 locations, we started to see signs of the issue that all small companies face as they scale – we were outgrowing our initial systems and processes and seeing decreases in efficiency and profits across the board. In fact, one day our President, Jason Owenby and I realized that we were making more profit with five stores than we were with ten. It was time for a change, but we didn’t have a comprehensive plan.

Our team and I had been working on solutions for about a year. Then I attended Tugboat Institute®’s Gathering of Teams in Nashville, and saw Bob Sutton speak. He was there talking about his recent book, The Friction Project, which I subsequently read and appreciated. Soon after, I mentioned his name to one of my regional managers, Joe Fowler, who suggested another one of his books, Scaling Up Excellence, which Bob had also co-authored with Huggy Rao. Luckily for us, it turned out to be a key tool in our efforts to scale.

While we never rolled the book out company-wide, it came at just the right time for me and the Leadership team and helped us in three distinct ways. First, it validated some of the steps we had already taken to change and confirmed that our instincts were on track and correct.

Second, it strengthened our resolve to press forward with some other initiatives that we were considering or that we had recently launched. And finally, it gave us some new ideas for ways we could improve that have ended up being pivotal for Jack Brown’s. Again, while we did not adopt every little thing the book suggested, the insights that helped us the most fell into three key categories: identifying and removing inefficiencies, reinforcing the right initiatives, and flattening the organizational structure.

As we’d grown, like many other organizations, when new issues presented themselves, we looked for and implemented a solution – to that specific problem. The problem was that this approach was almost entirely additive; over time, we found that we had accumulated a great many subscriptions, software programs, platforms, and processes that were unique and that served to handle one small part of our larger system.

The multiplying of a million singular solutions for each little problem creates a serious drag on efficiency. In his book, Sutton calls this “barnacles on the ship,” and his metaphor explains how they latch on individually and contribute to a general slowing down of progress. This was happening for sure. After reading the book, I realized we needed to get to work removing barnacles. Even better, I realized that we had a new initiative underway that was aimed at doing precisely this!

Our Director of Ops, Scott Krezmer, had recently undertaken the creation and implementation of something he called the Backpack. The Backpack is a central repository on the company’s internal website that houses everything managers need: marketing materials, scorecards, recipe guides, and inventory sheets. He even built an internal AI assistant – a golden cat, actually - that sits in the back end of our website and that can answer questions managers have about how the system works, where everything lives, etc. In short, the Backpack seeks to consolidate our many, diverse processes in one place, and streamline our systems. Scaling Up Excellence did not give us this idea, but it confirmed that we were on the right track, removing barnacles.

Another lesson we found in the book, and that spurred us to make some changes that were not already underway, were lessons about flattening the organization. Over time, we had created a pretty complicated communication structure, and as a result, the number of meetings created to make sure everyone was up to speed had multiplied. We had multiple layers of management and communication was neither simple nor speedy. This obviously led to delays and inefficiencies, and we realized we had a hierarchy problem.

The fix for this turned out to be relatively simple. Our leadership team began sitting in on regional manager meetings. This simple change dramatically improved communication, removed multiple players from the communication chain, allowed us to eliminate a great many meetings, and allowed decision-makers to hear concerns directly and respond in real time. Mike and I also launched the JB’s Founders Podcast for our team where we discuss company goals and ideas, share recent successes and celebrate our employees. Plus we get to share the fun and wild stories that come from running 20 bars.

A final lesson that has proven pivotal was around our team itself. We have always prided ourselves on being People First above all else, and of taking great care of our team. We realized, through reading this book, that we had perhaps taken this too far. Our joints were operating almost independently of one another. And in certain cases allowed people to stay who were not a good fit for the organization, in the name of being ‘good to our people.’ Sutton advised leaders to put the right people in the right seats. The work we had done on streamlining our systems allowed us to better articulate to our team what we stood for and what mattered to us, which in turn made it easier to identify areas where misalignment had set in. These changes led to a morale boost for everyone because they understood that we were willing to make difficult decisions for the good of the team.

As I look back on the lessons of the last year and the changes we’ve made, I can see clearly that we did the classic thing that growing businesses do. When we were small, we made a commitment to our People, and People First was the primary lens through which we evaluated all of our initiatives, our growth, and our decisions. When we finally realized that this had started to cost us significantly in terms of profits and efficiencies, we swung the pendulum the other way and entered a phase of hyper-focus on the numbers, KPIs, etc, at the cost, it turns out, of hurting some of our People First culture and programs. Scaling Up Excellence was the right tool at the right time for us because it helped us swing back the pendulum toward the middle.

And it’s working! In the past year, we’ve seen our culture and our purpose pervade the team much more powerfully and uniformly than it ever had, and we’ve seen profits increase significantly. Sutton also discussed creating a “common heartbeat” in a company, and seeking, as you grow, to build a “malleable prototype.” We’re only 16 years old and still learning. And in this line of work, the only thing that will remain constant, is change. We wanted to create a vision that everyone could align with, where they still had freedom, but within clear guardrails that defined what it means to be part of Jack Brown’s. We are looking through this lens now as we move into our next phase, and the difference is palpable. As we moved through all these changes, we took a year off from opening new stores to focus on getting our foundation right. Now, we feel more confident than ever as we prepare to open three new locations this year.

I am not saying that the book I read and what worked for us is the answer to every founder’s challenges as they face the problems that come with scaling. But if you are in this place, I do recommend that you look around for a tool that works for you. Whether it be a book, a consultant, or even a Tugboat talk, sometimes it helps a lot to feel you have some advice to lean on and at least the sketch of a path forward. It’s not easy to scale without losing what made you successful in the first place, but it’s the only path to long-term survival. We’ve been fortunate; by embracing a balance between structure and flexibility—between numbers and people—we are finding that growth doesn’t have to come at the expense of culture or profits. Instead, with the right approach, it can strengthen both, and more.

Building From Crumbs

Tugboat Institute® member Ford Mennel is the fifth generation leader of his family company, The Mennel Milling Company. In their 139 years, the company has been through many phases, some marked by prosperity and expansion, and some by stagnation and risk. Through it all, the series of family leaders who have shepherded Mennel have succeeded in building an Evergreen® company that is strong, continually expanding, diverse, and surprisingly innovative, given that their industry is one of the oldest in human society.

In this talk, Ford not only shares his family’s and company’s history, the risks they faced, and the strategies that allowed them to survive and thrive over time. He also demonstrates creativity in his approach to Pragmatic Innovation, not just in Mennel Milling’s products and services, but also in accessing capital for acquisitions while safeguarding the company’s Evergreen independence.

Watch and be inspired to be innovative in all areas of your company, and to build something that will last.

Onshoring as an Evergreen® Strategy

Dear Readers: This article was originally published in March, 2023. We are sharing it again today because its insights on onshoring strategies are particularly relevant amid the current tariff environment.

As businesses evolve and market conditions change, we as leaders adapt our strategies, experiment with new initiatives, build and rebuild our structures to maximize opportunities. In recent years, the shifts in the market have been dramatic and have caused us here at DEMA Engineering Company, like so many of you, to adapt and even roll back some initiatives that had seemed so right just a few years earlier. Some of these reversals have caused us to learn powerful lessons about what is right for an Evergreen® company in the long term, regardless of market conditions. Our journey to and from offshoring is a great example of this.

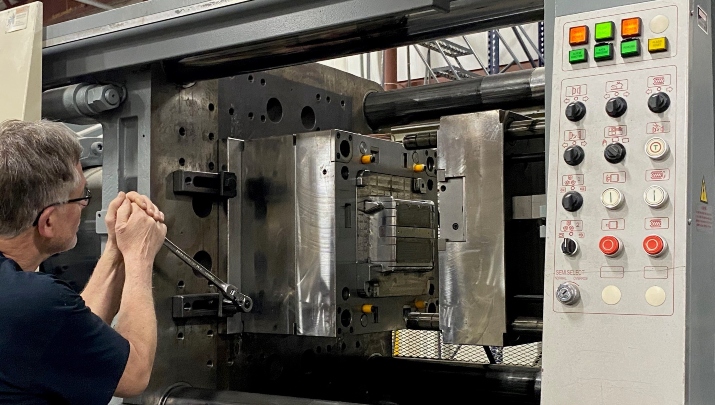

For us, the move toward offshoring started all the way back in the 1980s, when we started exploring some partnerships with companies who made injection molding parts in Taiwan. The reasons were clear; the cost of steel to make the tools and the cost of labor–and therefore the parts themselves–were far less than in the US. It was quickly becoming the case that making the tools necessary for running the injection molding parts, even more than making the parts themselves, was so expensive in the US that very few companies were doing it anymore. We found we had no choice, so we made the smart and obvious move.

This shift was happening on a huge scale, in manufacturing as well as a great many other industries. We chose to work with partners in Taiwan, with brokers who managed our relationships, instead of in China because we found that we were able to establish better relationships and communicate more easily, even though costs were higher there then in mainland China.

All of this became easier, even in China, in the 1990s. With the rise of email, communication became easier and more barriers to doing business in Asia fell. We were able to start doing direct sourcing, in Taiwan especially, and bypass the brokers, thereby reducing our costs even further. I don’t mean to minimize the role of China in all of this; we did and still do buy parts from China. It’s difficult to avoid. But it was not our primary market. For the last 20-25 years, our partnerships with suppliers in Taiwan became the core of our business for bringing in injection molded parts.

For obvious reasons, everything shifted suddenly and almost entirely in 2020. The biggest problem for us, as for so many, was the cost of freight, which had skyrocketed overnight. We went from a 40-foot shipping container costing $3,500 to costing over $28,000. You can imagine how much was dropping straight from the bottom line. Between the freight cost that had skyrocketed and the strikes in the ports, labor shortages, unreliable delivery timeframes, and all the mess we saw around covid, it was no longer workable and was imposing extremely challenging and unpredictable circumstances on our business. Add the price increases worldwide, geo-political challenges, tariffs– the uncertainty became too much. This is what pushed us to start to imagine a change.

As we started to imagine ways to mitigate this series of issues, we faced several challenges. One of the most significant grew out of the fact that, over the last 30 years, because of the situation I have described, production of certain products and processes, especially in injection molding, vacated the US almost entirely. For the molded parts, which were also hard to find, we made the decision to start molding them in the US ourselves, even though the cost was higher. We have done this in several ways.

We are able to source some of the parts right here in Missouri. We have a number of small partners here that we work with locally and we are growing that network. It’s not cheap, but we are saving on freight, and we have regained reliability when it comes to delivery times, which is huge for us. We also acquired a subsidiary company in Pennsylvania in 2006 that does injection molding, and since 2020, we have invested in that too, to help increase production. We are basically buying those parts from ourselves, so that helps mitigate the higher cost there, as we are supporting our own business. When we used to start a new project, we would go to Taiwan to get it going. Now, we are starting our new projects at home. We are carrying less inventory and we are being more strategic about the parts we do still ship from Taiwan, being conscious of the size and nest-ability, so we are shipping containers with less empty space.

All of this has helped us reduce our lead times, reduce the amount of money tied up in inventory, and regain consistency of both pricing and delivery of our products. Eliminating the wild uncertainty we were experiencing has been extremely important. But it’s a process; it will take time to truly complete this shift.

Today, we have brought back about 20% of the product we had been sourcing overseas. This number is going to continue to grow. Especially for new projects, we are bringing the tools themselves that make the parts back onshore, and then we can start making the parts here, in Missouri or in Pennsylvania. For the last three big projects we’ve done, we’ve been able to onshore most of the parts.

We regularly share this onshoring strategy with our largest customers and they are very supportive of these efforts. They also understand the benefits of reducing lead times and gaining predictability. Our business will never be entirely domestically sourced, but more and more is moving back home, and we feel very good about our decision.

I keep the Evergreen 7Ps® principles right here by my desk and I have been thinking about Paced Growth and Private in particular a lot recently. We wouldn’t be able to do this if we weren’t Private; it will take time for the investments we are making, especially in our Pennsylvania company, to yield results and return us to strong profitability. If we had a short-term mentality, we would have to follow the lower prices, like many of our competitors are doing. But we are diversifying and integrating at the same time, which will, in the end, make us a stronger company, better prepared to weather whatever the next 100 years have in store for us.

1,000 Years of Stewardship

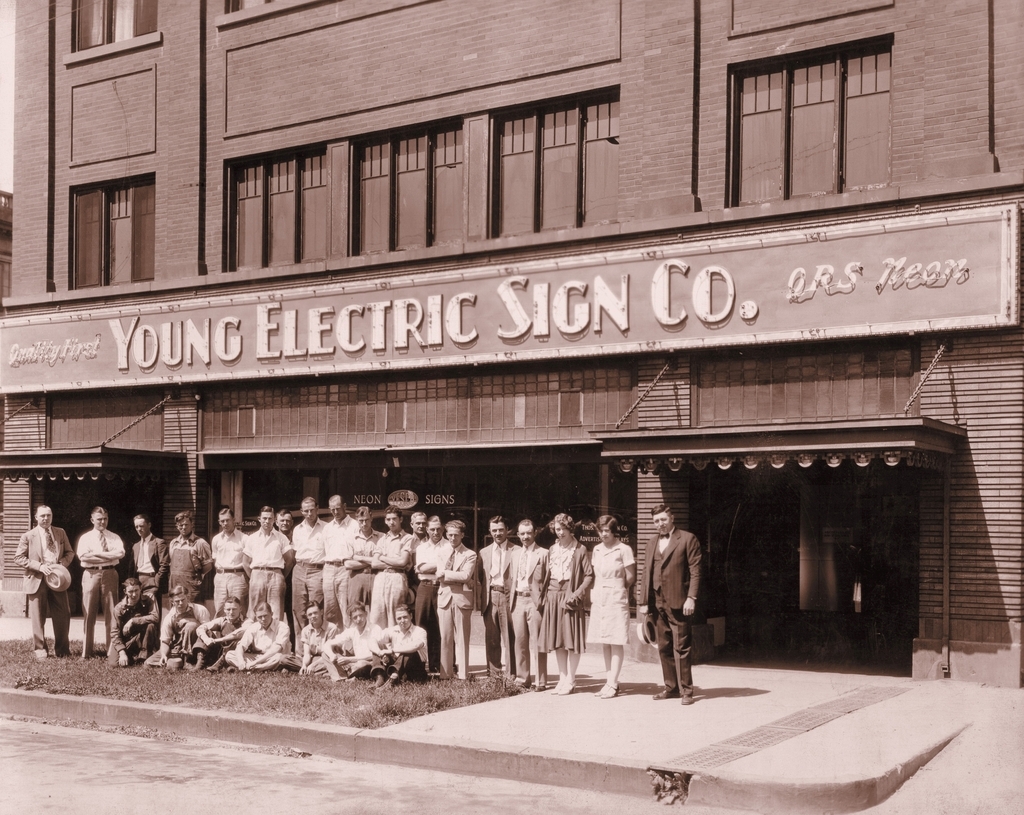

The story of the modern Western United States is a story of pioneers. My great-grandfather, Thomas Young, was one of these pioneers. He was drawn to these wide-open spaces by his faith and a belief that he could build a better life here. Leaving his native England at age 15, Tom and his family crossed an ocean and a continent, arriving in Ogden, Utah in 1910. Early on, he showed a talent for fine art. At age 20, the young entrepreneur founded Thomas Young Sign Company, specializing in hand lettering window signs. Neon was invented in France in 1910, and in 1928, Young purchased the license to manufacture neon signs in the Southwestern U.S.. The company name became Young Electric Sign Company (YESCO). Tom’s travels selling signs in Utah and California often found him passing through a sleepy rest stop in Southern Nevada called Las Vegas. In 1931, gambling was legalized in Nevada and the construction of the Hoover Dam began, with 5,000 workers pouring into the Las Vegas area. The first Las Vegas casinos opened, and by 1934, he had a make-shift office in the Apache Hotel designing neon signs by night and selling his designs by day.

Today, YESCO is a 105-year-old family-owned business with four primary sign manufacturing facilities and 36 sales and service offices in the Western US. We also operate a network of over 127 franchised sign and lighting maintenance offices east of the Rocky Mountains and in Canada. In 2021, I became the fourth CEO of the company, taking the place of my uncle who led the organization for 33 years.

At Tugboat Institute®, we talk about building companies that will last for 100 years or more. Outside of Tugboat, to non-Evergreen® leaders, this can sound ambitious and even unrealistic. So imagine the reaction I get when I tell people that we have just transferred ownership of our fourth-generation family business to a 1000-year trust! Yes, one thousand years. Here is the story.

My great-grandfather built his business for over 50 years, and while Evergreen did not exist at the time, his actions embodied the Evergreen 7Ps® principles. Recognizing the illiquidity of the company as he neared the end of his tenure, my great-grandfather realized he had a challenge to overcome. He had six children and liquidating the business could destroy everything he had built and endanger the jobs of his valued co-workers. So, he made a pivotal decision: he gave virtually all voting stock to one son, my grandfather, while non-voting shares were distributed amongst the other siblings. They each received some economic value from this arrangement, but my grandfather became the primary owner of YESCO. This ‘gift’ came with a very clear directive. My great-grandfather told his son that he had built the business alongside many great people, and that it was critical to him that those individuals be rewarded for their hard work. He told him that in handing him the reins of the business, he was charging him with carrying the torch forward, and to continuing to build something that would benefit all who participated in the effort. While Tom did not use the word stewardship, we have come to know that this is exactly what he was asking of my grandfather.

This arrangement did succeed in balancing control and economic value, though it also created tension and challenges within the family. YESCO did not, and still never has, made distributions to owners. Rather, it reinvests 100% of profits back into the business. This tension culminated in a major dispute that threatened the existence of the company. The dispute was ultimately resolved with a great outcome for the company and a modest share repurchase program. But the relationships between my grandfather and two of his siblings were permanently damaged.

Fast forward to the early 1990s, it came time for my grandfather to think about his own retirement. He was faced with similar estate concerns as his father. With five children, three of whom worked in the business, he sought his own solution that would preserve the company, and above all, the family relationships. His decision was transformative; he decided to make a move that would ultimately transform our family from a family of owners to a family of stewards. Rather than realize an economic windfall from his shares, he chose to gift them to the 100-year YESCO Stewardship Trust and passed leadership to my uncles and father, who would become trustees and stewards of YESCO.

A published article by family business experts Craig Aronoff and John Ward called The Critical Value of Stewardship was foundational for the development of our family’s creed and purpose. Here are a few of the core beliefs that came from this article and this period of transition:

• Stewardship is our duty to enhance the family’s resources for the benefit of employees and the community, as well as future generations of the family.

• Motivation inspired merely by increasing personal power and wealth fails to sustain families through the generations.

• The results of responsible stewardship provide the moral basis of private enterprise and justify the privilege of inheritance of private property.

• Having received the resources to continue creating value, subsequent generations must also accept responsibility and transmit talents and values.

• Personal well-being does not come from having money, but is achieved by building talents and character, experiencing accomplishment, learning from mistakes, and living with integrity.

So, how do you ensure that your children build character and that when they take over the company you built, they share your values and vision for the company and its future? Families have solved this problem in many ways, but my grandfather zeroed in on replacing the ownership mentality with a stewardship mentality. Both Thomas Young Sr. and Jr. hoped that YESCO could be a vehicle for future generations to be pioneers in their own right and experience the kind of happiness and accomplishment they had known. Their vision and hope were that YESCO would continue to bless the lives of not only their families, but also thousands of employees and the communities where they live.

In 2021, the third generation of the family began formally transitioning the stewardship of YESCO to the fourth generation. I became the CEO that year, with two cousins working in key leadership roles. Each of us began working with YESCO in our teens and experienced success in our chosen career paths within the company. My cousins and I are the first YESCO leaders who have never owned company shares. The YESCO Stewardship Trust allowed us to make this transition smoothly by passing the trusteeship between generations without conflict from shareholders, and without triggering any tax or liquidity challenges.

We realized, however, that there were still potential threats to our desire for YESCO to be Evergreen. First of all, almost 30 years had passed since the trust began, and it became clear that during our children’s lifetime, they would confront the termination of the trust. This would force the family to confront the issues of control and ownership. Secondly, our roster of non-voting shareholders had grown to nearly fifty, and with no distributions and little opportunity to sell shares, they were functionally bound as shareholders with their inherited shares.

In 2022, we became aware of a change in Utah’s trust laws which extended the permissible lifespan of a trust. We decided to take a bold step—transition from a 100-year trust to a 1,000-year trust. The transition was no small feat and took over two years to organize. It required revisiting and refining the trust’s language and intent to ensure alignment with the family’s vision. The process reaffirmed our commitment to stewardship and company values, as well as remaining an Evergreen company. We have also begun an enhanced share repurchase program to better balance shareholder needs for liquidity with company reinvestment. While this process could take decades to complete, our vision for the future is to maintain a roster of shareholders who remain by choice and are committed to our vision and goals, while at the same time creating an off-ramp for those who choose to leave. One of the unintended benefits of this process has been the mending of family relationships as we have reconnected with cousins who were once estranged.

Whether you are a pioneering founder or, like me, following in the footsteps of pioneers, I hope our story might have some lessons that can be applied to other companies who aspire to endure the next 1,000 years. The whole idea of a business existing, and leaders serving as stewards for the benefit of others is at the core of the Evergreen movement. As I look to the future, along with my leadership team, we are clear that we aim to make YESCO an incredible place to work and grow responsibly, so when it’s time to hand over the reins, we can say we’ve honored the trust.

Fireside Chat with Dave Thrasher, Dan Thrasher, and Dave Whorton

Dave and Dan Thrasher grew up in the house that served as the first HQ for their parents’ basement waterproofing company, which they had started and grown slowly over decades. By the time the two brothers stepped into the business, their parents had grown it to about $4 million in revenues. In the 20 years since then, Dan has taken over leadership of Thrasher Group, Dave leads the newer company, Supportworks, and together, they have built their companies to an impressive $400 million in revenue.

In this Tugboat Institute® Fireside Chat with Dave Whorton, Dave leads the brothers through stories from their childhood, their entry into the business, and the birth and growth of their respective companies. In their conversation, they cover topics ranging from early forays into entrepreneurship, what they learned and have preserved from each of their parents, key moments through the growth of the business, both before and after they joined, and the effect of the arrival of PE in their space.

Watch and be inspired to lean into your values, make courageous decisions, and find new ways for your business to grow and thrive.

Paving a Path to the Trades for High School Graduates

The last decade has seen significant social and economic ups and downs, but from a business owner’s perspective, one thing seems likely to remain constant: workforce shortages in skilled trades will only continue to grow. This has affected us at Lozier Corporation, a leading manufacturer of products used by retailers and warehouses: store shelves, backroom storage, sortation solutions and checkout and self-checkout systems.

More than a decade ago, we realized that our skilled trades workforce was retiring faster than we could fill those roles. The knowledge gap was only likely to grow, so we decided to work toward diffusing it. Our most successful effort so far has been an initiative designed to engage high school students and introduce them to the opportunities that trade school can provide. Through this work, we have not only helped solve a critical labor shortage, but we’ve also provided young adults with an education at no cost to them, as well as a viable, stable career path.

Lozier is headquartered in Omaha, Nebraska, with facilities across the US. In Omaha, and now in Scottsboro, Alabama, we have created a program that is building us a robust pipeline for developing skilled tradespeople, thereby addressing our workforce needs.

When we first perceived this issue, the average age of our skilled trades employees was between 55 and 58 years old. It was clear that this created a looming retirement cliff. With fewer workers entering the skilled trades field, and demographic data that suggested this would only get worse, we saw that we were on the verge of a critical shortage of trained employees in essential areas like electrical, mechanical maintenance, and tool and die. We had to get out in front of it.

Our options were limited. The first option was to enter an expensive bidding war for existing talent, but this brought with it obvious disadvantages far beyond financial, as that talent was harder and harder to find. We decided we could do better and partnered with the local community college to help develop our own talent, proactively.

Inspired by some others in our industry in the U.S. and especially in Europe, our Chief People Officer and a dedicated community outreach specialist led the charge to develop a training and apprenticeship program aimed at cultivating a new generation of tradespeople from the ground up. A significant advantage was that, by creating our own program, we could tailor it to meet Lozier’s specific needs. The groundwork required to get it started included an enormous amount of community outreach and forging of relationships with local schools and organizations, but in the end, that work, and those relationships, have become the reason it has worked so well. It also confirmed one of the competitive advantages of being an Evergreen® company: people and relationships contribute value that compounds over time.

Lozier’s program, now well-established in Omaha and in Scottsboro, operates on a multi-faceted approach, each aspect of which is designed to benefit both the company and the individual who engages in the process.

A critical piece of the program is the early outreach and recruitment. In an effort to connect with high school students while they are far enough along on their journey to have started to think about life after school, but not so far that they have committed to a specific option, we engage directly with local schools. We visit students at school, we invite students and their families to visit our sites, and we work with Career & Technical Education teachers to identify promising students with an interest in skilled trades. Our focus is to educate the students, the educators, and the parents about the great career opportunities in manufacturing at Lozier. While high school seniors are the primary focus, the outreach efforts often begin earlier, sometimes in even middle school.

Students selected into the Sponsorship for the Trades program receive myriad benefits. Upon graduating high school, selected students work for Lozier and then enroll in the local community college to pursue an associate degree, at no cost to them (books and tools included), while continuing to receive paid, on-the-job experience at the manufacturing company. Upon completion of their education, the student is guaranteed a full-time job with benefits at Lozier.

One of the most innovative and fun aspects of our program are our Signing Day Ceremonies. Each Spring, we host a formal event equating signing to a career in the trades to signing to a college to play sports. These days are designed to celebrate the students and their bright futures, and we involve families, teachers, current and former Sponsorship students, the community and invite the local press. This public recognition helps to elevate the trades as a respectable and desirable career choice.

In order to make the associate degree piece of the program possible, we collaborate closely with local community colleges to provide formalized training at the same time as students are gaining hands-on experience in our plants. The opportunity to earn a degree, all while getting paid, and then start a full-time career without any college debt at all appeals to a great many young people and can be an excellent opportunity to launch into their professional lives and feel quite far ahead of the game.

The impact of this initiative has been significant. Approximately one third of our current skilled trades employees have come through this program, effectively closing the gap of the talent crisis we perceived a decade ago. What began as an effort to merely survive a labor shortage has evolved into a thriving, self-sustaining talent development pipeline and transformed individuals’ lives.

In the time since we have started this program and through its growth, it’s been interesting to watch national trends around post-secondary education. In the U.S., parents and educators used to prioritize four-year college paths over the trades. This contributed in large part to the shortages we saw coming down the line that inspired us to begin this work in the first place. But as college costs continue to soar, the national perception of skilled trades has shifted dramatically. An increasing number of students do not want to start their professional lives saddled with debt, and they are starting to see that they don’t have to; there is another path. Our program, while initially slow to attract applicants, now receives more applications than available spots, making participation increasingly competitive.

Beyond direct workforce development, this initiative has created a ripple effect within the communities we serve. Several former Lozier tradespeople have transitioned into teaching positions at local community colleges and high schools, bringing real-world experience into the classroom, reinforcing the value of trade careers, and further strengthening the relationships that we have forged with the local schools and community colleges.

With our Omaha and Scottsboro programs running successfully, we now have our sights set on expanding the initiative in other locations. However, it’s a big undertaking; such programs require long-term commitment and resources to be effective. For example, Lozier attended and participated in 96 school events in the 2023-24 calendar, along with 34 community events. To support these events and activities, 38 employees volunteered their time. We have learned that in order to be effective and take root in the community, we have to be ready to commit for real and for the long term. We have to take the time to build relationships, set a foundation, serve a small number of people initially, and build a meaningful presence in the community. With time, trust is earned, and success begins to compound.

While the skilled trades labor shortage remains a nationwide challenge, the model we have developed provides us with strategic investment and community engagement. We have been able to both secure our own future workforce and also provide young people with stable, lucrative career opportunities. We are an Evergreen® company whose Purpose is our people. We want our people to become better versions of themselves and to have the opportunity to improve their lives, take care of their families, and give back to their community. This initiative has allowed us to serve our people, and to improve and strengthen our business at the same time.

In closing, I’ll share a few words from one of our newer hires, Sam, who is in Tool & Die. Sam summed it up succinctly, but in some ways, he said it all; "Don't second guess the trades, because we need trades more than ever."

Innovating Through Values-Aligned Partnerships

My father founded the Larkin Company in 2001, after selling the first company he co-founded that administered self-insured disability benefits. The Larkin Company also manages employee benefits, including disability and leave of absence services, and focuses on providing customized, People First solutions for each company’s specific needs. People typically go on leave for reasons that are associated with a huge life event, which means they can be emotional and often difficult situations. We are in this industry because we believe we can help make people’s experiences easier and more positive, by connecting people with the right people and building solutions that matter. This is, we believe, what differentiates our Evergreen® company from most of our competitors.

At the same time as we are driven by a desire to be People First, we are a business, and we must continue to grow and evolve to stay relevant, successful, and Evergreen. For this reason, we are always looking for ways to be innovative and take advantage of opportunities that present themselves, in as smart and creative a way as possible.

The initiative I am going to share with you today grows out of these dual perspectives of the Larkin Company: to take good care of people, and to continue to grow and evolve in our changing market.

As is often the case with the best ideas, this one came to me not because I went looking for it, but because life brought it to my door, in the form of a deeply personal experience. My wife’s father started to decline, and she faced the daunting challenge of navigating healthcare, benefits, and resources for him, a task that proved to be overwhelming and time-consuming. As I watched and helped her navigate this difficult journey, I was struck by how nearly impossible it was to manage these responsibilities while maintaining a full-time job.

From this realization came a broader recognition: many employees, especially those in the “sandwich generation,” are stretched thin, balancing care for both their children and aging parents, not to mention their responsibilities at work. These are often unplanned emergencies, such as a parent’s sudden fall, requiring immediate action and extensive navigation of healthcare and benefits systems. It is rarely possible to manage this and stay productive and focused at work, but there is often no alternative but to do as best as one can. Often, the only choice is to take a leave of absence from work which is when they call The Larkin Company. Seeing the gap in support available to employees, I wondered, could we help make this journey easier? Are there services we could provide, better than what an employer may find through an EAP, that might help the employee and either alleviate the need for a leave of absence entirely or at least reduce the amount of time needed away from work.

Through our personal experience, we had met two women who had just launched an eldercare startup called Ways & Wane. They had done several years of research and had worked hard to lay the foundation for their business. We thought, why not benefit from this hard work, and at the same time, help them get their new business off the ground? We invested in their company, becoming part owners, and set out to bring an eldercare service to life, in partnership with Ways & Wane.

Founded by two sisters, this small company already had a road map for eldercare services navigation, and our investment allowed them to scale and integrate the service into our broader offerings. Rather than building from scratch, the partnership fast-tracked the solution, capitalizing on the startup’s groundwork and building from our shared vision for high-impact, employee-first care. This partnership appealed to us in great part because the founders of Ways & Wane shared our People First orientation. We were a great match.

Like the rest of our services, the eldercare navigation service we developed together places empathy at the core of the solution. Our high-touch model ensures employees have a supportive guide who walks them through every step, from understanding Medicare options to exploring VA benefits for veterans. The service even includes personalized research, like identifying suitable care facilities and ensuring they meet the necessary standards. This matches the level of care we provide for other leave and disability benefits, so it fits right in with our larger profile of offerings.

Feedback from clients has been overwhelmingly positive. In fact, for some of our larger corporate clients, eldercare support has become the top-rated employee benefit within its first year, with participants praising the relief and clarity it provides. Sometimes, employees access eldercare and are able to successfully navigate their situation without taking any leave at all. Many employees have shared that the guidance they received made their process so much easier and more efficient that it prevented them from needing to take extended time off work, which of course benefits both the employees and their employer.

Could we have opted to start our own elder care division, from the ground up? Given that we operate in an adjacent industry, of course we could have. But it would have taken time. The decision to partner with Ways & Wane saved us so much time and money that it was an easy decision to make, particularly given that we are so values-aligned with the co-founders. At this point, Ways & Wane has expanded to cover children as well. So, the solution is evolving into a full family care package. We have a similar collaboration with Navvisa, a startup specializing in cancer care navigation, which grew out of the same strategy: identify critical employee needs and invest in solutions that bring immediate value. Mental health is another area we see opportunities in the near future.

Despite the advantages of the partnership and the relative speed with which we were able to put this initiative into action, it has not been perfect. Our eldercare service has seen slower-than-anticipated adoption—partly due to market conditions and company cost-saving measures. However, the feedback has been so consistently positive that we are optimistic. Given the demographic realities of the country, this is a need that is not likely to abate any time soon, and as it becomes adopted by more companies and normalized, we expect it will continue to grow. Recall that not much more than a decade ago, parental benefits were not mainstream. I was involved in that work at the time, and it took a while for that to get going and for people to see the value of it. But today it’s more or less standard; I think the eldercare piece is following the same trajectory.

From the employer side, it’s a classic win-win. By reducing or even eliminating the need for leave altogether, this service saves companies money on backfilling positions and maintaining productivity. Employees feel supported, and employers see the financial benefits. I can’t imagine that this is going to do anything but continue to grow, especially as people are living longer and longer lives.

To me, this initiative is all about balancing empathy with strategic investment. By listening to the real, often emotional needs of employees and finding agile ways to address them, we are finding more ways we can create meaningful support systems that benefit everyone involved. Taking good care of people isn’t just good ethics—it’s good business.

The Science of Happiness and Social Connection

Dr. Sonja Lyubomirsky is an experimental social psychologist at University of California, Riverside. She has been studying the science of happiness for decades and her work has included consulting on projects like the film Mission: Joy, featuring the Dalai Lama and Bishop Desmond Tutu.

In this Tugboat Institute® talk, Sonja poses the question, “Is it possible to become happier?” and shares the findings from her many years of research in order to answer it. Happily, she found that there are many things we can do. Even better, the most powerful ones align with Evergreen® best practice behaviors.

Watch and be inspired to take steps to increase your own happiness, and to connect with others at the same time.

Discovering Evergreen

As most of you are aware, Dave Whorton and I have written a book about Evergreen® businesses—or rather, more precisely, about Dave’s discovery of the Evergreen way of building and running a company. Until then, the Evergreen companies had been completely unrecognized as a business phenomenon, not to mention a critical component of the American economy.

I had been introduced to Dave by his erstwhile partner Chis Alden, who had approached me about attending the second Tugboat Institute® Summit in 2014. I was the co-founder of the Small Giants Community, based on my book titled Small Giants: Companies That Choose to Be Great Instead of Big. Alden thought some members of the community might be interested in attending the conference. I couldn’t make it, but I was fascinated by the concept, especially given its unlikely origin in Silicon Valley, the last place you’d expect to find any interest in private companies that eschewed venture capital and never intended to be sold. I resolved to find out more and possibly write about it for Inc. magazine, where I was editor-at-large at the time.

Toward that end, I introduced myself to Dave and met him at his office in Palo Alto in mid-December 2014. We chatted about the Evergreen companies in his institute. They sounded a lot like some of those I had met through Inc., including one in particular, SRC Holdings—formerly Springfield Remanufacturing Corp.—of Springfield, Missouri, with whose co-founder and CEO, Jack Stack, I had written two books. During the meeting, I suggested that Dave read the first of those books, The Great Game of Business. A couple of weeks later I was surprised to learn that not only had he read the book right after our interview but he’d arranged to visit Stack in Springfield.

I continued to do research for an article. Among other things, I attended the next Tugboat Institute Summit in Sun Valley, Idaho. I had recently published another book, this one titled Finish Big: How Great Entrepreneurs Exit Their Companies on Top and, at Dave’s invitation, had agreed to give a brief talk about it. The experience at Summit gave me a better sense of the organization he was building and the business leaders he was attracting. I was most struck by their determination to build companies that would last much longer than they themselves would be around to participate. I decided to make the companies’ longevity the focus of my article for Inc.

My editors loved the idea, and I thought they would make it the cover story, but—as the publication date approached—I was told that the magazine had a big “scoop” that it would have to give priority on the cover instead.

The “scoop” turned out to be what my editor described as an “exclusive” interview with Elizabeth Holmes, the founder and CEO of Theranos, manufacturer of a supposedly revolutionary new blood testing system. Sure enough, the October 2015 issue appeared with Elizabeth Holmes on the cover portrayed as “The Next Steve Jobs.” Also mentioned was my story about building companies that would last 100 years or more. Two weeks later, the Wall Street Journal published the first of John Carreyrou’s exposés about Elizabeth Holmes and the Theranos fraud, for which she was ultimately convicted and sent to prison. My article about Tugboat held up considerably better.

Thereafter I continued to follow Dave Whorton and Tugboat Institute, attending Tugboat Institute Summit every year. I was very impressed by the company leaders whom I met there—the lengths that they went to support their people, the role that they played in their communities, their attention to the quality of the products and services they offered their customers. I included several of their companies in the monthly column I was then writing for Forbes.

It occurred to me that many more people would like to hear the story of Tugboat Institute and how a former venture capitalist wound up starting it. I had been writing about business for almost 40 years, and I had never heard or seen any article or business school course about companies that followed the Evergreen 7Ps® principles (Purpose, Perseverance, People First, Private, Profit, Paced Growth, and Pragmatic Innovation) that Dave had identified as the defining characteristics of Evergreen companies. I could see they constituted an important part of the economy that had heretofore completely escaped the notice of the wider business world. When Dave happened to mention that people had suggested he write about the subject, I jumped at the chance to volunteer my services. And that’s how this book came to be written.

We did it with long interviews that I arranged to have transcribed. Then I worked with the transcriptions to produce a draft that Dave would change as he saw fit. What interested me most in working on the book was the opportunity it offered to examine two totally different concepts of business—or actually three, if you consider that Kleiner Perkins exposed him to two ways of building companies with venture capital. All of them can produce significant companies. The approach people prefer depends in large part on their values and goals. Dave Whorton thought that the best businesses would do what Bill Hewlett and David Packard had done with their company, Hewlett Packard—that is, build a community that not only makes great products for customers but fosters better lives for the people who do the work required. Dave Whorton’s experience gave me new insights into how it is done and specifically how the Evergreen companies go about it, which is the subject of the book.

My hope is that readers will appreciate the role of those companies play not only in shaping our economy but in enriching our world. I also hope that readers who start their own businesses will see the Evergreen model as one worth pursuing themselves.