The Pre-Mortem

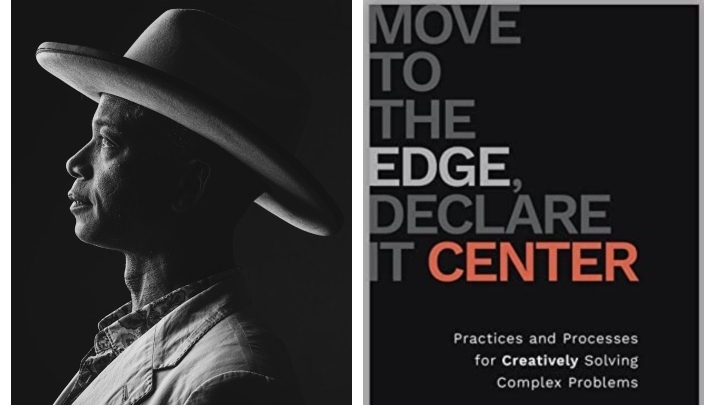

- Everett Harper

- Truss

In his new book, The Power of Regret, Daniel Pink argues that regret is not a negative emotion we should seek to avoid, but rather a positive one. It is regret that allows us to examine our mistakes and learn from them, so we don’t repeat them over and over. But what if you could take it one step further and learn from your mistakes before you even make them? At Truss, we have been working to learn from potential mistakes before we make them through a process called pre-mortem.

Pioneered by Gary Klein in 2007, the pre-mortem was designed to reduce the frequency of failure and is based on a psychological principle called a counterfactual, which asks how you can imagine something that has not yet happened and, further, how you can draw use from that imagined future. In contrast to the post-mortem, which examines the outcome of an initiative once it is over, the pre-mortem also focuses on a specific initiative, but ideally before it begins or in its early stages. Here is what it looks like.

As you prepare to launch a project, you assemble your team. You tell them, “I want you to imagine six months into the future. The project has launched, we are well into it…and it’s been a complete failure. Our colleagues, customers, and partners are all angry or disappointed, and we are embarrassed”

Pause. Let that sink in.

Then you ask, “What happened?”

Usually when I first launch this question into a room, I am met with silence. We aren’t used to being asked to express vivid failure, and there’s often a bias for keeping our doubts silent. As a leader, I often start myself; I imagine a failure that is grounded in my own error or oversight. When the team sees that the potential problems could implicate even the CEO, they become more willing to play along. A good practice is to have everyone write their thoughts down first. This has the advantage of ensuring that your team members are sharing independent, diverse perspectives. Eventually, your team starts sharing: we took a risk on pricing and didn’t react quickly enough when we needed to adjust; we didn’t execute our media strategy properly; our competitor came out with a better product right after we launched. We encourage team members to share potential failures grounded in both internal and external factors, and we get it all on the table.

Sometimes the ideas get ridiculous, but even those are important – having a laugh can reduce the hidden anxieties of the team in a safe way. The goal is to get as wide a variety of possibilities as possible, and ideas that come from each person’s specific area of expertise. It can get quite lively once you get going, and you start to realize areas where you need to protect the project in a way you hadn’t previously imagined. Then, as a team, we look at all the ideas we have generated, organize the fixes for the mistakes we haven’t made yet but might make, and set about implementing them. Now your team has action items, they have learned from each other’s perspectives, and they have the time and the clarity to work to mitigate the bad outcomes you have imagined. The subtle but crucial key is for the team to invest in imagining a vivid outcome of failure. By doing this, they will usually uncover new obstacles that they can fix together. It is remarkably effective.

One concrete example of a time when we used this at Truss was back in 2017, when we were considering making salaries internally transparent. We were interested in improving equity and thought this would be an effective way to do that. Before we made the decision, we did a pre-mortem. We asked ourselves, what could go wrong here? Well, people could dislike it so much that they would leave the company. That would be a terrible outcome. How do we mitigate the risk of that happening? To solve for this, we decided to find out ahead of time how people felt about it. Simple, but we hadn’t planned it initially. We polled our employees, asking them if, hypothetically, they would be for or against this move. We learned that most were for it, and we learned what the specific concerns of those who weren’t sure were. We were able to fix those issues before we made the shift and, importantly, before they became big problems.

Another way you might use the pre-mortem is directly with your clients. It requires a great deal of trust so I might recommend that you have a few cycles of project execution, postmortems, and addressing issues first. This establishes the practice that postmortems are about learning, not blaming, and following through with actions tends to increase trust. As you build trust, you can introduce the pre-mortem before the next initiative. When we do this with clients, they initially can’t believe that we are willing to consider that we might make a mistake. But then they start sharing things that they are worried about that we might never otherwise have known. The practice of pre-mortems has been an incredibly useful practice for building client trust, mitigating risk, and planning successful projects.

I use this process in my personal life as well, such as when I chose between grad schools. When I have a big decision to make – especially when I am deciding between two great choices– I created the habit of writing myself a letter. In the letter, I imagine I have chosen either option A or B, and I am several months into my life post-decision. The crucial step is to write out in vivid detail what that future life in choice A looks like: where I’m located, who I interact with, how I feel, even the sights and sounds. One of two things usually happens. Either I know within a couple paragraphs that choice A is wrong, or I get excited by my description of the future. Then I put the letter in an envelope, put it on my mantle, and open it again six months later (yes, I’m old school, you can do it electronically and set a reminder). At that point, I am well into the reality of life post-decision and I can compare the two versions. It allows me a window back into my thinking when I made the decision, and the opportunity to re-evaluate my choice. Often, it turns out to have been the right choice, but sometimes it doesn’t. By reminding myself of my original intention, I can correct course, move forward, and re-evaluate how I made the decision, given the information available. This sometimes is the most powerful part of the practice of using counterfactuals to make better decisions.

This is a quick overview of a complex process that is highly Evergreen®, because it empowers all team members to contribute, in a risk-free environment, to problem solving and troubleshooting. It can influence how you make decisions, what level of trust you enjoy within your team and with your clients, and even how you think about future endeavors.

There is obviously no way to clearly see what really does lie ahead, but the learning that can come from this peek into the future is profound, meaningful, and actionable. We get the benefit of learning from mistakes that Daniel Pink advises us to embrace, but we get to do it ahead of time, when there is still time for our learning to influence the present. It’s the best of both worlds.

Everett Harper is CEO & Co-Founder of Truss and author of Move to the Edge, Declare it Center, where you read more on practices like the pre-mortem.

*photo credit: Asa Mathat

More Articles and Videos

Both/And Thinking: Harnessing the Positive Potential of Tensions

- Marianne Lewis

- Carl L. Linder College of Business, University of Cincinnati

Leading Through Uncertainty – Tugboat Institute® Summit 2025

- Jackie Hawkins

- Tugboat Institute

Get Evergreen insight and wisdom delivered to your inbox every week

By signing up, you understand and agree that we will store, process and manage your personal information according to our Privacy Policy