What George Washington Can Teach Evergreen Entrepreneurs

- Stephane Fitch

- FitchInk

The entrepreneur’s life seems to involve endless toil and anxiety punctuated by the occasional success and, sometimes, an hour of cheerful distraction. That’s how it is for me, anyway. So when I strolled into a primitive flour mill at George Washington’s Mount Vernon estate in Alexandria, Virginia, one evening in October, I thought I was in for the distraction part of my chosen field.

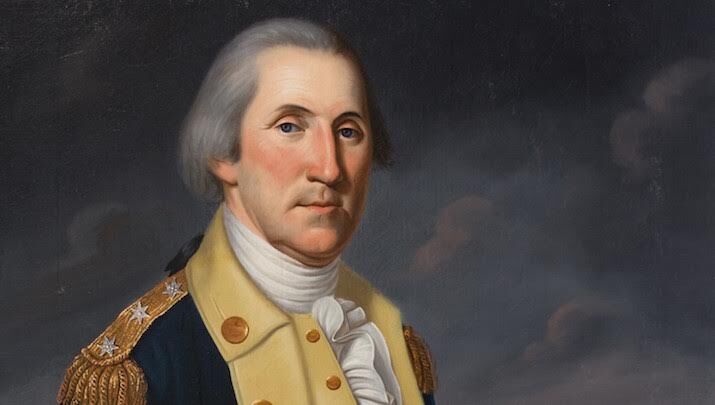

I assumed Washington’s famous plantation would serve as a mere backdrop for the intensive two-day leadership workshop the Tugboat Institute set up for us. Hell, what could a wealthy ex-president in a powdered wig possibly teach a bootstrapping tech-savvy modern businessman like me?

I soon had my humbling answer: a lot.

Washington was, in fact, a vigorous entrepreneur and innovator. The lessons he learned managing his business affairs at Mount Vernon helped win the Revolution and shape the world’s idea of democracy and free enterprise. Yeah, Washington would have been a fabulous mentor.

By the way, he didn’t wear a wig. Or chop down a cherry tree, sign the Declaration of Independence or use wooden teeth. He was fortunate, sure. Washington’s family owned land and slaves and his father, Augustine, successfully farmed tobacco. Yet Washington’s life was full of challenges. When he was just 11, his father died. Washington’s uncles didn’t provide him with a formal education. In fact, Washington took his first job at age 15. A relentless reader, he was self-taught, and expected the same of the others he was leading. He believed a person can control how prepared he is for success, but not success itself. Like many of the greatest modern entrepreneurs, he had no college degree.

But was he Evergreen? Would he have nodded knowingly at the Evergreen 7 Ps? I think yes.

Purpose. After eight years leading the Continental Army to victory — Washington did it without pay — he formally handed back to Congress his commission as commander in chief. In London, George III asked the American-born painter Benjamin West what Washington would do now that he had won the war. “Oh,” said West, “they say he will return to his farm.” “If he does that,” said the king, “he will be the greatest man in the world.” Washington would repeat this act by serving as president of the United States for two terms and returning to his farm. Unlike most other revolutionary leaders — Napoléon, Stalin, Cromwell — Washington walked away from power twice to serve the public good.

Perseverance. Washington understood that perseverance was in itself the key to victory. During the eight years of the Revolutionary War, he lost more battles than he won. Through seven winters, he never left the Continental Army’s encampments, even during the famously frigid winter of 1777 to 1778, when he and his men trained and suffered at Valley Forge, 20 miles north of Philadelphia. Throughout the war, he avoided a single climactic battle that could have wiped out his army — until his decisive win at Yorktown.

People First. As a battlefield general, Washington learned (after many defeats on the battlefield) to listen carefully to his lieutenants — unlike his British counterpart. The habit stayed with him as president, when he relied heavily on the advice of brilliant (and often rival) cabinet members like Alexander Hamilton and Thomas Jefferson. And yet he owned hundreds of slaves. “People often ask us if George Washington was kind to his slaves,” said our Mount Vernon tour guide. “The answer is that there is absolutely nothing kind about slavery.” That said, Washington willed that more than 100 of Mount Vernon’s slaves be emancipated upon Martha Washington’s death — an act that no other slaveholding president, not even champions of human rights like Jefferson and James Madison, repeated.

Private. The notion of taking private ventures public was gaining steam in Washington’s day. The Philadelphia Stock Exchange was founded in 1790, and Washington did form a joint equity enterprise to improve navigation on the Potomac — the investors’ capital went to build canals around waterway hazards in the river, benefiting all. Yet Washington kept his Mount Vernon enterprise private. And he never indebted it so severely that lenders could pressure him for control.

Profit. Washington was intensely mindful of profits and always wanted to maximize the value of what he produced as markets changed. Though he had to abandon day-to-day management during the Revolution and later as president, he constantly wrote letters to his managers at Mount Vernon inquiring as to the farm’s operations and profitability. He invested in thousands of acres of land around the country, and he was arguably the wealthiest president in U.S. history.

Paced Growth. Washington sought opportunities for paced growth even in the last years of his business life. His operations expanded from tobacco to wheat, livestock, sheep, a mill, a fishery, a self-sustaining estate and more. After leaving office in 1797, Washington returned to Mount Vernon and, with the encouragement of his farm manager, James Anderson, entered the whiskey-distilling business. Though Washington lived only two years after leaving office, these two were his most profitable ever. In 1799, his distillery produced nearly 11,000 gallons of whiskey, making it the largest whiskey distillery in America at the time — yes, even bigger than Jacob “Jim” Beam’s.

Pragmatic Innovation. Washington was fascinated by new labor-saving technologies and made a lifetime commitment to practical experimentation. He kept regular correspondence with other thought leaders to keep on top of market changes, best practices and new technologies. He played a major role in developing America’s mule population and pioneered various agricultural methods. “He not only signed Patent No. 3,” notes Robert Shenk, senior vice president at George Washington’s Mount Vernon, he “also installed the automated mill technology (as a licensee) into his Mount Vernon gristmill described in that patent.” At Mount Vernon’s flour mills, he paid dearly to import highly advanced French millstones whose carved milling surfaces could cut wheat and other grain with scissorlike precision. The resulting flour was fine, pure white and highly valuable. It would pass for what a modern baker would refer to as “cake flour.”

So what did it all mean? I have heard Dave Whorton, head of the Tugboat Institute, argue that the concept of running a business in an Evergreen way is revolutionary but not really new. It’s part of an old but enduring tradition that the world has forgotten how to celebrate. It was inspiring to consider Washington’s life as evidence that Dave is right.

Yes, Washington probably would have called Mount Vernon Evergreen. And maybe, one of our lecturers commented, his greatest Evergreen project was the United States itself.

Stephane Fitch is the CEO and Founder of FitchInk.

More Articles and Videos

Both/And Thinking: Harnessing the Positive Potential of Tensions

- Marianne Lewis

- Carl L. Linder College of Business, University of Cincinnati

Leading Through Uncertainty – Tugboat Institute® Summit 2025

- Jackie Hawkins

- Tugboat Institute

Get Evergreen insight and wisdom delivered to your inbox every week

By signing up, you understand and agree that we will store, process and manage your personal information according to our Privacy Policy